GIST may be something that you’re living with for a very long time.

It’s important to remember that GIST can evolve over time, and so too might your treatment needs.

Given the rarity of this disease, the expertise of GIST specialists is crucial for effective disease management.

GIST stands for Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor. It’s a soft tissue sarcoma that can occur anywhere in the digestive tract (GISTs primarily develop in the stomach, accounting for approximately 60% of cases. About 35% occur in the small intestine. Less commonly, GISTs may also originate in the rectum, colon, or esophagus). Very rarely, a GIST can happen in the abdominal cavity—this is called an eGIST.

You, your care partners, and your care team may have all been surprised by a GIST (gastrointestinal stromal tumor) diagnosis. After all, it is a fairly rare condition with 4,500 to 6,700 new patients per year within the European Union. While GIST can occur at any age, it is most commonly diagnosed in individuals in their mid-60s.

It’s not clear exactly what causes GIST. No lifestyle or environmental risk factors have been identified, though most people with GIST do have a gene mutation, which may drive tumor development. Why that mutation happens to some people has not been determined.

If the GIST tumor can be removed with surgery, it’s known as “resectable GIST.” Advanced GIST is defined as GIST that can no longer be treated with surgery alone, or has come back, or has spread to another part of the body.

Disease progression means that cancer cells may be growing, the tumor may be getting bigger, or it may be spreading. Disease progression can happen if genes continue to change (mutate), which means that someone with GIST can have new and different mutations over time. If that happens, a treatment could stop working, even if it worked before. This is called drug resistance. You should always speak to your doctor about your GIST treatment. You may not be aware that your GIST treatment is no longer working, or you may develop new symptoms that signal something is wrong. Because it may be hard to tell on your own, it’s important to have follow-up appointments and tests with your care team.

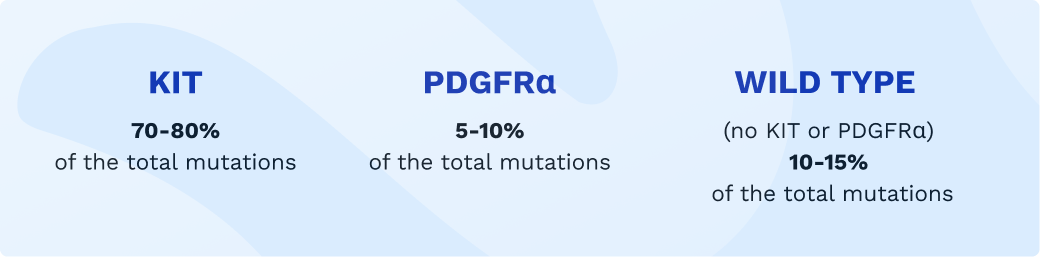

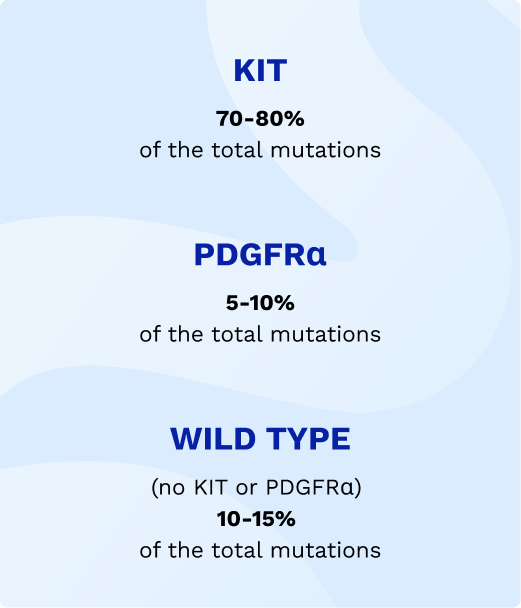

Many doctors also recommend genetic testing (or genotyping) before prescribing a treatment. This might be helpful because some drugs target certain genes associated with cancer. And some genetic mutations can affect how well certain drugs work. You may be tested for KIT (exon 9, 11, 13, and 17) and/or PDGFRα (platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha, exons 12 and 18).

Your main follow-up might include imaging, CT (Computed Tomography), MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging), PET (Positron Emission Tomography), FUSION PET‑CT (a combination of Positron Emission Tomography and Computed Tomography), and/or blood tests. These will help monitor your health and ensure that your treatment is effective. They help keep track of any changes and make timely adjustments to your care plan if needed.

Not sure what to ask at your next GIST doctor’s appointment?

Download here a guide to support your discussion with your doctor.

Primary mutations are responsible for starting the growth of GIST.

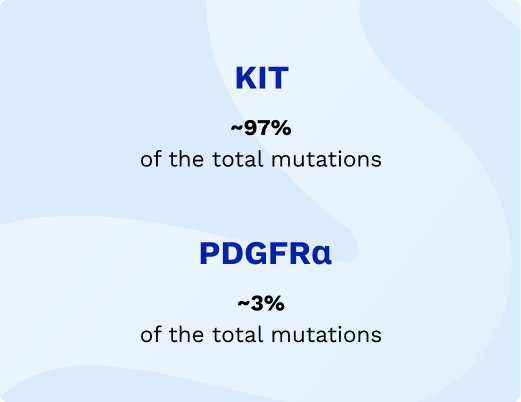

In people with GIST, the most common primary gene mutations are:

Sometimes, genes can continue to mutate.

Over time, someone with GIST can develop new and different mutations, called secondary mutations.

Sometimes, genes can continue to mutate. Over time, someone with GIST can develop new and different mutations, called secondary mutations.

The most common secondary mutations in people with advanced GIST are:

These secondary mutations are relevant because they can affect how well treatments continue to work. In some cases, they may cause resistance to a drug that was previously effective, making it necessary to adjust or change the treatment plan.

All cancers, including GIST, begin when one or more genes in a cell mutate. A mutation is a change that is usually caused by damage to genes in a cell at some point during a person’s life. It’s not clear why this happens.

Genes make proteins that control how cells work. Mutated cells can create abnormal proteins or prevent proteins from forming. Either can cause cells to multiply and become cancerous.

Your doctor may recommend that you get genetically tested for your mutation as part of your GIST treatment. Knowing your gene mutation type can help your doctor give you the best possible treatment and avoid drugs that may not work well. For some patients with low‑risk GIST, your doctor may decide mutational testing is not necessary.

Primary mutations are responsible for starting the growth of GIST.

In people with GIST, the most common primary gene mutations are:

Sometimes, genes can continue to mutate.

Over time, someone with GIST can develop new and different mutations, called secondary mutations.

Sometimes, genes can continue to mutate. Over time, someone with GIST can develop new and different mutations, called secondary mutations.

The most common secondary mutations in people with advanced GIST are:

These secondary mutations are relevant because they can affect how well treatments continue to work. In some cases, they may cause resistance to a drug that was previously effective, making it necessary to adjust or change the treatment plan.

Not sure what to ask at your next GIST doctor’s appointment?

Download here a guide to support your discussion with your doctor.